Welcome to article #2 in this three-part mini-series on Top-Down & Bottom-Up designing for interactive streaming and MILEs!

Now that we’ve (re)explored the concept around Top-Down / Bottom-Up design, let’s look at specific applications within the area that interests us.

This will seem, at first, like a strange place to start but let’s briefly look at how interactive streaming projects can fail.

We observe two common fail states:

- The framing device doesn’t match with a good interactive experience, so people are excited by the premise but don’t go beyond their first try OR;

- While fun, the interactivity feels gimmicky and doesn’t go beyond the stage of technical demonstration – the participants don’t invest further time into it.

You want to provide a reason for people to want to care (vision), as well as a way for the participants to take part that is compelling (mechanics).

A combination of these two principles is ideal – a stated vision for participants, combined with new ways to interact that were limited in other forms of media. Using both at once helps to avoid the most common pitfalls of just using one of the two approaches – making it best to combine Top-Down and Bottom-Up design processes to succeed.

Let’s spend some time on each process separately before combining them.

Are they, as an example, a divine avatar splintered into millions of component pieces? Muses? Or something less abstract – say birds that can peck to make the actor not as keen to visit the seaside where there is a warehouse with some secret documents.

It’s not always possible to have a full answer to what form the participants take, but considering the question as a designer already has value because it considers the self-identity of the most common human that interfaces with a MILE. A good way to teach this to the participants themselves is to show that by interacting with the world they are observing functions, since participants can then perceive themselves, and more importantly other humans, as having that ability.

Going with the other approach of “Bottom-Up”, especially if you are starting with interactive streaming, tends to be more frequent – you have access to a new technology suite and an experience you likely already made so it makes sense to try novel mechanics within the realm of a world that is already created (or planned to be). And in reality, it’s recommended as part of the discovery process – by taking the time to tinker around with the possibility space in a way that’s familiar, it becomes easier to visualize what you can craft.

Without a way to communicate to viewers what is going on in a verbal or visual manner, it usually leads to confusion for them. And the communication is different, because they won’t necessarily interact – telling a viewer that they can interact but also that they don’t have to is complex, especially the latter. This is where looking back through a top-down vision can help (which is often best done, but not forced to be, from scratch – either as a new project or a special mode).

Let’s cut to the chase and do both approaches at once.

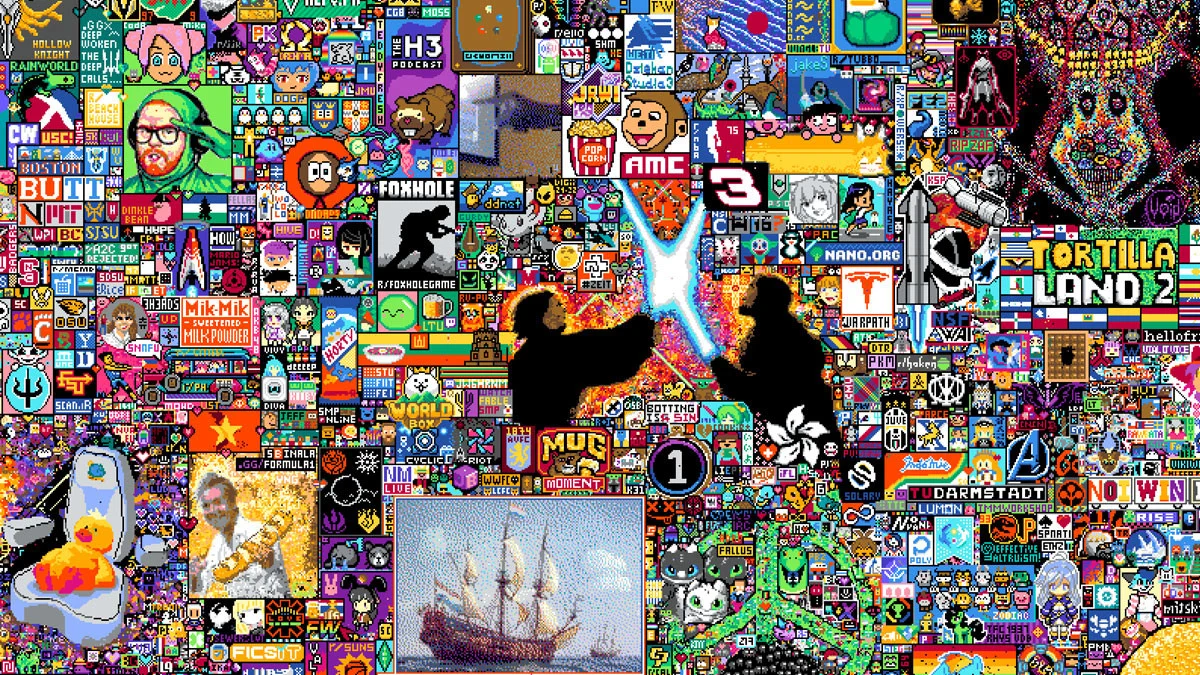

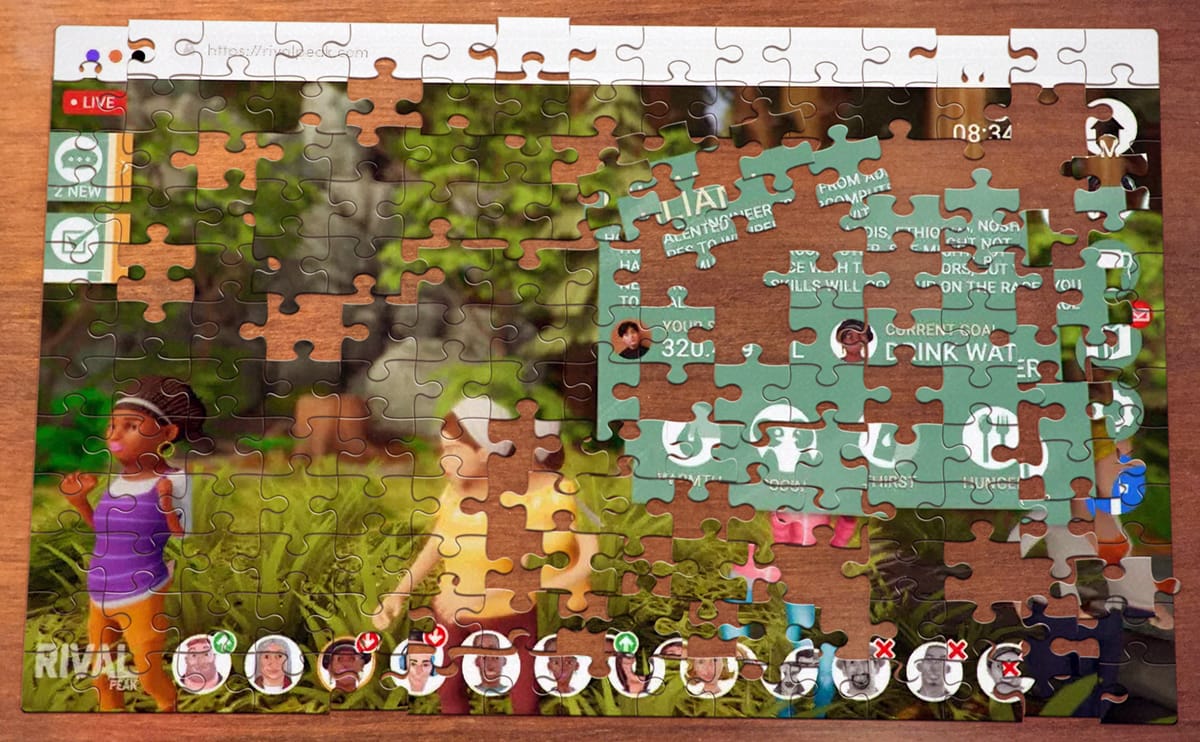

By doing both Top-Down and Bottom-Up, we get to look at opposing points; one focused on the overall vision, one focused on the direct feeling of taking part. Similar to how a jigsaw puzzle is best solved by starting with the corners and edges before building inwards, we can define the outward points of a cylinder and slowly start filling the gaps in between. Descending into the center then becomes a question of starting from each point, going towards the middle and meeting there.

Going from top-down:

- At the very top is the vision of the MILE;

- Within that step, we can consider who the actors, participants and viewers are;

- Descending a step, we start looking into vision communication – how to make it clear to participants the nature of the world they are experiencing, what they are watching in context and how interactions affect the world (note – this is not trying to teach control on the environment but to communicate to viewers that the environment is alterable);

- In the middle – what am I saying about the experience (from a narrative point of view)?

Going Bottom-Up in a similar fashion:

- We want to start with an interactive mechanic – something simple that acts as a hook and allows viewers to transform into participants;

- Then comes a harder mechanic to create – how to make viewers feel as participants without the need to interact (a key phrase – “presence matters”);

- In the middle – what does a participant say about the experience (from the point of view of mechanics)?

Here is a table to recap the above:

| Vision (Top-Down) | What is the narrative framing of the experience? What are the participants / what do they represent? |

| Vision Communication to Participants | How do I understand the vision visually? What am I seeing on screen that allows me to understand the world? |

| Enjoyment Testing | What would a participant typically say after taking part (narrative / mechanic)? |

| Example Mechanic – Passive Presence | A mechanic where the participant doesn’t need to take action but they have a potential effect on the experience. |

| Example Mechanic – Interactive Presence | A simple mechanic that is self-focused where a viewer can interact with what they are watching |

In the next article, we’ll fill this table step-by-step, looking at how to further embellish it and have a useful framework to use for your own projects.

See you there!

Join our Discord Server to discuss this article with our team.