Why we care about giving the best possible experience to everyone

When technology leaps forward, people get left behind. Often the mundanity of economics is the gatekeeper: expensive new devices and services price people out of the latest innovations. Geography, infrastructure, education and language can all be barriers too – even the well off and fortunately located can find themselves frozen out of experiences because of disabilities if their needs haven’t been considered.

Whatever the reason, many of the world’s most vulnerable people are frequently left in technological ghettos, the inequalities they already suffer compounded by their lack of access to our latest advances.

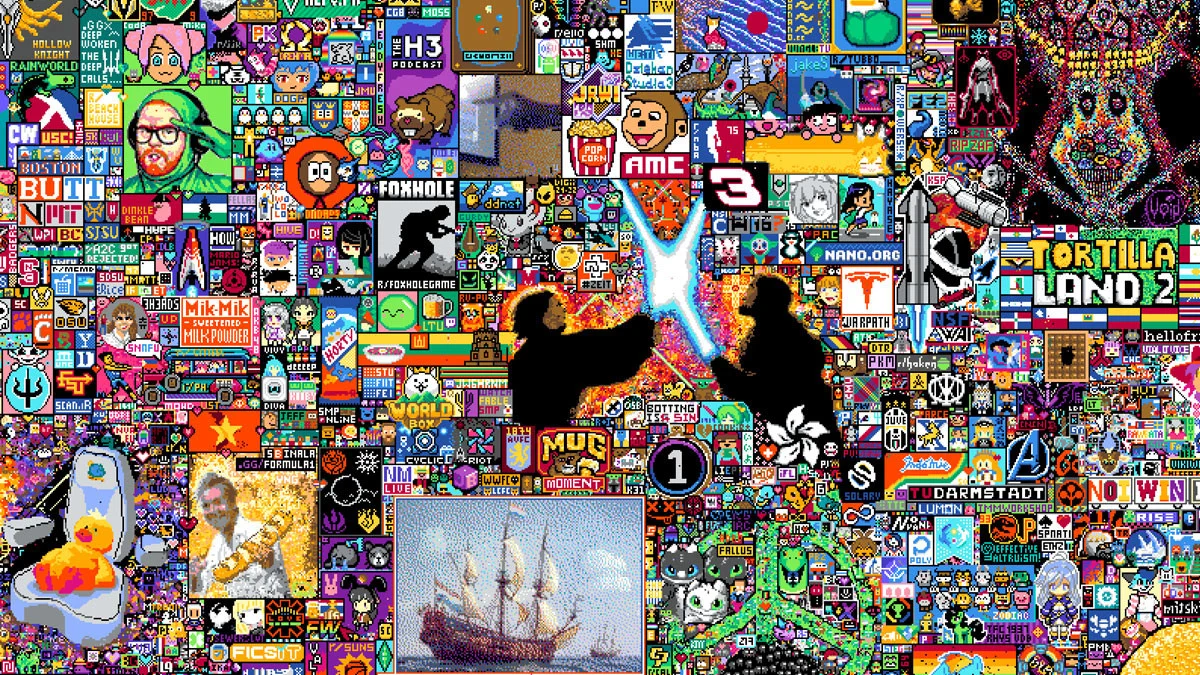

Last year, I was lucky enough to moderate a discussion on this very topic – focused on the Metaverse and how we can ensure it’s as accessible as possible. I proposed this panel because Genvid’s core technology, and the concept of Massively Interactive Live Events, or MILEs, which sits at the epicentre of our business philosophy, are something which we hope to see play an important role in the Metaverse: shared communal virtual experiences with meaningful interaction and the lowest possible barriers to entry.

Accessibility is also a foundational ethos at Genvid: our software can run MILEs on almost any video-capable connected device, on any video-streaming platform, with no downloads. We want to ensure that the experiences we facilitate are open to the widest number of people possible.

Evolving necessity

Currently the Metaverse is nebulous. Usually, technical advances begin as luxuries, but successful luxuries become commonplace – TV, radio and even literacy were all once the domain of the wealthy, after all. More recently, the Internet transformed the cultural landscape, moving from futuristic curiosity to essential service in just a few decades, and was defined as a human right by the UN in 2011. In practical terms, just how important it has become to modern day life has been starkly illustrated over the last 18 months.

During the pandemic, the Internet played a vital part in keeping people connected and healthy. The elderly, a group at high risk of death or long term complications from the virus, suddenly found themselves unable to take visitors, to get on public transport and visit shops to buy food. Instead, they had to learn how to video call on often unfamiliar devices, order online food deliveries from supermarkets, and source reliable information about how the situation was progressing.

Children, learning from home via video call, suddenly needed at least one internet-capable device each, complete with camera, to access education. Even in the UK, the world’s 5th largest economy, 73% of school leaders stated that their pupils had insufficient access to the internet and technology to adequately learn from home. After over a year of this enforced deprivation, their education and prospects had suffered greatly.

Infrastructure

This isn’t emerging technology. The Internet has been a commonplace factor in the developed world for over 20 years, all but ubiquitous and sometimes the only available way to get something done. Most of us are steeped in it, fully online in almost every aspect of our lives, and yet there are 85 countries in the world where less than 50% of the population has internet access. That’s hundreds of millions of people. In the US alone, where 95.5% of the population is online, over 15 million people still can’t use it. The lack of access to the internet in developing countries has been identified as a key factor in their continued exclusion from the global economy – a catch 22 with no immediate solution.

All this goes to say that new technology disseminates quickly amongst the privileged, becoming integral to modern life, yet very slowly to those who remain. Which means that we need to be extremely cautious when transferring vital processes to rely on these technologies, and also that we should be attempting to mitigate these barriers to entry at the earliest possible stage of design and development.

That brings us back to the Metaverse, a much-vaunted next great leap for humankind which is hoped to bring unparalleled community, connectivity and richness of experience to our society in the coming years. That we’re moving forward this quickly whilst so many are still catching up on the last few decades illustrates both admirable and lamentable qualities of the human race, but that’s another essay entirely – what I want to focus on in the blogs which will follow in the coming months is how we should be aiming to avoid the Metaverse becoming the domain of a privileged few and instead make it accessible to as many people as possible, with as diverse a cast of architects, contributors and denizens as we can.

In each, we’ll look at the various barriers to entry for the Metaverse, how we can mitigate them, and what thinking needs to be done in the planning, architectural, regulatory and implementation stages of any endeavor which purports to be truly inclusive. The first barrier I’ll examine is internet access – something unavoidably fundamental to the experience of the metaverse. It’s something that’s very easy to take for granted, even for those of us who grew up without it, but just a little research shows that reliable internet is nowhere near as universal as it may seem. If we don’t solve that problem before addressing the next, the most vulnerable will find themselves not just one, but several steps behind.